Update: This post includes content from a few others on the issue. Over the last few days, readers here and elsewhere have shared some very compelling thoughts. For a roundup of ideas offered on this topic, from comments across this blog and elsewhere on the Internet, please see my newest post on the issue.

For a broader look at constructing a relationship between readers and writers when covering rape and trauma, see my January/February 2011 article in the Columbia Journalism Review (PDF here with permission).

For suggestions about meaningful consent in trauma journalism, check here.

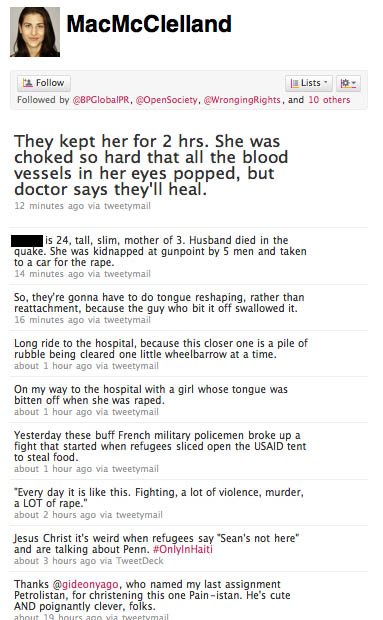

Following a reader’s wise suggestion, I have blacked out the woman’s real name in the screen shot below of Mac’s twitter feed. Her real name was originally broadcast on Twitter but the magazine eventually ceased using it, substituting an initial.

Okay, all I know so far is what Mac McClelland is telling me. But it’s creeping me out.

She’s live-tweeting the story of a rape survivor. Live-tweeting the interview, I assume. I heard about it @MotherJones, where Mac is a staff writer and has done some stupendous, we-should-all-thank-her work on the BP oil spill/scandal. I also really love Mother Jones, which is still ballsy enough to be home to important reporting. But this wasn’t so well thought out.

MoJo retweeted staff writer Stephanie Mencimer‘s tweet: “Awesome @macmcclelland is tweeting a horrific story about rape survivor in Haiti. Follow, but be prepared: serious stomach turning. Follow!”

I heard about it 30 seconds before I clicked on Mac’s Twitter feed and took the screen shot below. That was 20 minutes before I wrote this blog post (based on my Twitter status). So I don’t know what’s happened since the screen shot.

I have three problems — huge, huge problems — with this:

1. Basic 101 of interviewing trauma survivors* is to make sure they’re in control of the experience that is the interview. Why? Common human decency is one reason. Another reason is that the experience they’re telling you about is one of utter powerlessness; it’s your duty as a journalist to restore as much power to that re-telling as possible.

That includes, I think, letting them tell the whole story before you broadcast it to the world. There may be details that they don’t get right the first time and they call you to correct. They may tell you something that later they regret and ask you not to use — and it’s within your rights as a journalist to grant that request, if it doesn’t compromise the story. The point is, they need to have the power to ask.

2. Basic Trauma 101* is that the trauma narrative is often confused for survivors — although “confused” is valued language that comes from the world of the non-trauma survivor. For the trauma survivor — and especially for survivors with PTSD, who are literally re-living the story, sometimes as they tell it to you — time is not sequential. The story does not come out in a chronology. (And for a really good book about this, and how important it is to listen as long as you need to, as many times as you need to, to understand, see On Listening to Holocaust Survivors by Henry Greenspan.)

Why’s that relevant here? Two reasons. One, Because presumably you’re asking the survivor to share her story for some larger purpose — presumably there’s something others need to understand by listening to her. Otherwise it’s just voyeurism, and you should go home. (I’m not accusing Mac of voyuerism.) But you need to listen through the whole story to understand what that is, and then you need to frame it for us.

Two, you just un-ordered her story because the medium demands it. The nature of her experience may also have un-ordered it. This is closer and more literal to the risk that is “journalism as trauma” than I am comfortable with.

3. If she felt that her story were best served by live-tweeting, she could do it herself. Journalists presumably bring editorial skills to a survivor’s story that the survivor values. If tweeting the rape story is the way to tell the rape story, then we don’t need the journalist.

Update: Since this post got picked up by The Altantic Wire, I’d like to pull from another post the following and put it here, because I think it’s important:

One, you can handle all those concerns I raised above and tweet the story responsibly — if you don’t do it live. Use the digital illusion of a story you’ve already reported unfolding in real time over Twitter; you don’t need to actually be there tweeting it as it unfolds. I still think Twitter is too ephemeral a tool for something as serious as rape, but this is one way to do it more responsibly.

Two: To write responsibly about rape, you have to think not only about the rape survivor who is your subject — although that’s primary — but about your reader, as well. If you’re reader can’t figure out how you got the information, they’re going to be ethically uncomfortable.

I saw that in other people’s responses to the “rape feed.” The journalist didn’t explain the rules of the game before starting; she just launched in. We didn’t know what we were in for — it did, indeed, look at first like we were going to get a grisly rape story, tweet by tweet, and then the story changed. We were in a doctor’s office. But how did we get there? Do we feel okay about being there?

For example: Tweeps (I hate that word) had concerns about whether the victim had given consent and whether she should be named. I didn’t share these concerns — I gave MoJo the benefit of the doubt on both — but clearly Mac/MoJo would have done everyone a favor if they had stated this up front.

There’s a fine line for journalists who cover trauma. How do you balance making the reader ethically comfortable with you, the journalist, and making the reader morally uncomfortable with the violence that happens in the world?

This is what trauma journalists are trying to do. They aren’t sanitizing stories or giving you the “golly gee whiz I came through it stronger” hopeful Hollywood ending. They are trying to be honest about the story, and honesty about brutal violence should make us uncomfortable. That has to happen. But readers shouldn’t ever feel uncomfortable about the journalist’s practice. The minute the reader stops trusting the journalist, the story is lost. And that’s a disservice in many ways, but above all to the woman who’s story the journalist was trying to tell.

One more thing: Mac’s newsfeed goes straight from “whatever I was just thinking” to “now I’m telling a rape story.” That’s jarring for “readers.” Also, the self-promotional background seems incongruous to the subject (I didn’t include it in the screen shot, but it’s wallpaper of the cover of her book on Burma). I’m not trying to be snotty here; I think it’s a real concern.

Someone on Twitter told me, “Not every story needs to be told in every medium available.” I think that’s right — and as cool as this whole social media thing is, we need to be extra careful about using it responsibly. Because if we’re not, then we are getting dangerously close to voyeurism, whether or not we intended to.

To MoJo if they come across this: What was the editorial discussion that went on before this feed started? What kind of editorial direction is Mac getting as she tweets?

*For absolutely essentially professional resource for journalists covering stories of trauma and survival, please (please, please) visit the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma.

Jina you do a great job at highlighting the issues, and I think this article is presented excellently. I’d like to add to your points, in a much less partial, potentially more confrontational manner.

1. Stephanie Mencimer referring in the initial tweet to this as “awesome”. Is offensive and disgusting. At what point can you ever preface “horrific story about rape survival” with awesome?

2. How can this reporter possibly be giving the survivor the attention she deserves, if she is tweeting while “listening”. In the short, she can’t. Not only will she be missing parts of the story (either through verbal or non verbal clues), in my humble opinion, it adds to the survivors re-victimization. How can you show the necessary empathy or concern if you are distracted by your concern to “live tweet” to your audience?

3. “Just because you can…doesn’t mean you shouldn’t” The plethora of social media available is fueling our voyeuristic and car crash watching tendencies. Now if you want to look at the car crash all you have to do is google it. Where I live, a 16 year old girl was gang raped last weekend, and the pictures were disseminated on facebook. The police pulled them down, but these pictures have now gone viral. How could anybody with a conscience actively search and view these pictures.

Similarly why would anybody want to watch a live tweet of a rape interview? If you really want to learn about this victim, the circumstances, the greater purpose of discussing rape in Haiti should we not wait until the article is published?

Isn’t really the only purpose of reading these tweets – to fulfill our human voyeuristic tendencies or in tweeting – to boost our readership?

Just because we can, doesn’t mean we should.

Interesting post. I can’t really decide if I’m for or against it. In terms of telling a genuine story, though, I would think the Tweets represent the raw data, the raw experience, free of editors and shaping and crafting. It’s like the story in its purest form. Why can be live-blog riots and election results and not this? Isn’t this the story in its purest form?

(Not trying to pick a fight. It’s a tricky issue — one I’m probably not qualified to deal with).

I’m a little uncomfortable with the word “raw” but I get what you’re saying. This wasn’t tweeted by a survivor herself; if it were (and obviously if it weren’t coerced), I’d say I that I have nothing to say about that. It’s our choice what we do with our experiences. But the journalist who tweeted it has as much discretion as editors of a print piece to “shape and craft” — in fact, has all that discretion. So I don’t see the “purity.”

But for the record, I think “purity” is a poor standard, because it is an illusion. “The story in its purest form” doesn’t exist. Hell, we all mediate ourselves, to ourselves, just to live with ourselves every day. More importantly, I don’t think writers and editors shaping and crafting are unpurifying a story. I think writers and editors know how to make a story make sense to readers. Reread any first draft of anything you’ve ever written for proof of how difficult it can be to convey something… I think we need to respect what writers an editors do. I think we need it.

If you really want to use “raw” as an argument for tweeting this story, I would like to make the argument that this is not exactly purely “raw” because

a) McClelland has to do the typing and for sure unless she is typing verbatim, it is NOT a raw interview,

b) the actual event of the rape has already passed, so the point of “raw” is really missing here,

c) readers who often do not have experience doing their own primary research imagine that the “raw-ness” of a data is the most interesting part of it but little did they know the amount of work it takes for the journalist (and anthropologist) in order to compose a story and analysis. If you don’t believe me, try your hand at it by going through “raw” historical archives and see if the pieces and bits of information by themselves are all that interesting. No they are not because it requires someone to “cook” the data (make sense of the data) before it gets interesting. You can also comb through the “raw” data of an anthropologist’s fieldnotes and see that they are often very boring and tedious to read without them being “cooked.”

d) you’re also not understanding the point of self-presentation in everyday life. A victim or an informant is going to speak and present the story in a different way if it is going to be in an interview form versus if he or she is going to stand up in an auditorium and craft her own story of the experience. This is not to say that one version of the story is more true than the others. It is to say that we always filter our experiences and the way we present the information is partly dependent on what kind of venue we are under. 99% of the time, if you listen to raw interviews that most journalists and anthropologists do, you’re going to have to do a LOT of your own work in order to make the interview interesting.

Finally, my own peeve is this: what the heck is the interest that Americans have with “raw”? Sometimes the understanding of “raw” is so naive and simplistic! Segments of the American public think that “raw” means “truth” because “obviously” if we hear the story live from the victim’s mouth it must totally be 100% true. Well, if you turn into a self-reflective mode, you can see that experiences you have and then talk about are never exactly the way the experiences are because there are so many ways to capture an experience. Experiences are multi-dimensional whereas speech (interviews) are linear because that is how it is.

Anyway, enough of this nonsense!

Thanks for sharing a social science perspective on data, “raw” or otherwise, and self-presentation. I appreciate your insights.

I would love to hear a debate between you and Mac McClelland. As an anthropologist, I do NOT believe it is okay to tweet these stories. What is the point of doing these things by twitter? More to the point, what is the point of allowing uncooked data be fed to the public?

Building rapport is not just a one step process nor a one moment process but continues with the informant throughout the entire interview and even post-interview. The journalist (and anthropologist, for that matter) needs to be able to digest the story before telling it. Likewise, the victim also needs to be given the space to speak her story before it is solidified via twitter.

McClelland is not very sensitive to the question of self-presentation (see, for example, Erving Goffman), it seems. Twitting an informant’s speech live is akin to putting the informant on public stage or live television without giving the informant the benefit of the spatial cues and social dynamics that would indicate this is a live event. Once the informant can feel that this is a live event, what he or she say will be very different than an interview which even though will be publicly produced as an article, is NOT uncooked and raw, thus giving the informant (victim) more space to think out loud rather than having to commit to each and every word they say on the onset it leaves their mouth.

McClelland to me, seems to have thoroughly violated ethics that journalists supposedly are taught (ethics that anthropologists definitely are taught too) for the sake of perhaps making the story “live” and “raw”. Maybe if she can provide a good reason why this story needs to be twittered instead of “cooked” by forming into a published story, I can think over if her arguments has any merits. For now, I am quite dismayed at McClelland.

I like what you said about trust because certainly I have lost trust in McClelland. To tweet a story (interview) live is to say:

1. this hasn’t gone through my discerning mind thoroughly before I type

2. I am more interesting in the live factor of the medium than respecting the rape victim, respecting myself as a journalist, and respecting my readers

3. I am more interesting in giving you my initial sense of what is interesting to say, without realising the consequences of doing that.

In Chinese, we say this way of doing the story hasn’t gone through the “big mind”, which is to say it wasn’t thought out carefully because it was done at the spur of the moment.

Why, McClelland? Why?

Well-said, Jina, and glad to see that the Atlantic Wire picked it up. I wish every journalist had to take a course on covering trauma. Understanding the very specific dynamics of these situations – like that someone who’s recently been raped might not be capable of giving informed consent – is so important to remain ethical in reporting on these very real tragedies. I just hope McClelland had enough sense not to use the woman’s real name.

Thanks. That’s an excellent point — consent in the immediate aftermath of trauma. “Yes, it’s fine” isn’t the same thing. Especially if saying yes to the journalist seems to you like the only way to get your ride to the hospital.

This raises a more fundamental issue for me and that is the appropriateness of journalistic interviewing of trauma survivors by anyone not trained to properly understand the phenomenon of trauma.

I sense a horde of journalists getting their backs up already, reading this as an outsider’s criticism etc etc etc. I was a journalist for more than 15 years before I moved into humanitarian aid. This is NOT a comment from someone with some innate hostility to the profession. At all. This is (hopefully) constructive input from someone who has trained and worked in both of these realms. Please read what follows with that firmly in mind.

There’s a lot about the way trauma operates that is not obvious to those who’ve not had some training on the subject. This means that untrained interviewers – however well-meaning and careful – risk inflicting additional harm on someone who has already endured enough. It’s not enough to be a caring, sensitive person. Some of the dynamics at play in cases of trauma can seem quite counter-intuitive.

In the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake I listened in horror to several well-meaning interviewers blundering through exchanges in which they prodded survivors to relive their experiences. Their increasing distress was excruciatingly apparent to me but seemingly not to the interviewer. I wondered whether there would be any proper support in place for the interviewees – several of them children – once the recording was finished, but I doubted it; anyone sufficiently aware of the need to provide follow-up support would surely have realised that the interview should have been halted much much sooner…

We also have to take enormous care on the issue of informed consent. Someone who has experienced a traumatic event almost certainly does not yet know how the psychological impacts of that experience will manifest over time. Responses to trauma are extremely individual and can emerge over a timeframe much longer than many of us realise. A survivor cannot be sure today how it will affect him or her in a week, a month or six months to come face-to-face again with their account of their experience, or someone else’s reflections on the events in question.

I would, in a general sense, advise against publishing/broadcasting this kind of interview in any situation other than one in which the survivor actively pursues the opportunity to put her/his experience into the public domain.

Even then, journalists have a moral obligation to do what they can to ensure that the survivor’s decision is not just free, but also *informed* in regard to the possible impact on their long-term recovery. And if there is any doubt about whether trauma might be impacting on the survivor’s capacity to make an informed decision extreme caution is required. Is it really essential to go ahead with the interview now? A decision to delay leaves the door open to go ahead later.

In some cases public testimony is empowering, while in others, encountering replays of the interview or the response of people who heard it or just the survivor’s resulting loss of control over who knows can be crippling…

I would call on all responsible journalists to insist on being provided – or for those working independently, taking the responsibility upon themselves to obtain – some basic training on trauma and dealing with survivors. Even a relatively short introduction can be invaluable in equipping you with the knowledge you need to avoid inflicting a great deal of unnecessary harm on the people you might encounter in the wake of armed conflicts, natural disasters or other personal tragedy.

Thanks Robyn, for that dual-profession perspective. The Dart Center on Journalism and Trauma provides just that kind of training, and I hope interested journos (and others) will check it out. (Links in my posts.)

There is no context in these tweets.

They read like gruesome tabloid headlines.

I’m trying to figure these things out:

Was she interviewing the victim or someone with the victim?

The woman’s tongue is mutilated, and the reporter is interviewing her? How can she talk? Interviewing her presumably thru a translator? (double the torture)

But then I go see the rest of her tweets and see it’s probably the victim’s mom talking – in which case, we don’t even know if victim agreed to this.

Further tweets reveal the victim indeed remains very upset because she glimpses one of her rapists outside the car during the interview. And the reporter herself is tweeting outrage at doctor treatment of the victim.

It’s all undigested upset from all angles. Unedited, un-contemplated. Great, if you’re narrating the fall of the world trade center; not so great with the very personal disaster of a human who can’t even talk because her tongue was just bitten off in a rape.

And what’s the rush with this story? Is someone going to scoop her?

Robyn, you wrote this:

[quote]

We also have to take enormous care on the issue of informed consent. Someone who has experienced a traumatic event almost certainly does not yet know how the psychological impacts of that experience will manifest over time. Responses to trauma are extremely individual and can emerge over a timeframe much longer than many of us realise. A survivor cannot be sure today how it will affect him or her in a week, a month or six months to come face-to-face again with their account of their experience, or someone else’s reflections on the events in question.

[/quote]

EXACTLY! I TOTALLY AGREE! While I’m an anthropologist, my training does not involve working with trauma victims. On the other hand, having had long term field experience (2 years immersed in the field), I am totally aware that even with non-trauma victims, when informants give informed consent they don’t necessarily know the possible consequences of their own words and thoughts and how that may or may not affect their position in the community, their position with their family etc.

Because the anthropologist is in the field spreading out feelers and getting hooked into multiple networks and various social relations, we learn a lot about people in a way that if one were to simply live in an everyday way, one wouldn’t. Because of that, when I have conversations with informants or more formally have interviews with them, I also realise that I cannot simply blurb out everything they say to anyone else (even though they’ve given informed consent), because a) I have to consider what are the consequences for him or her in the community or in the family if I do that, and b) what are the consequences for me with regards to my standing within the community or the families I know in the community.

So, if I were not to give that much thought, I would very easily have done harm to both informant and to myself if I didn’t think through carefully how information I gathered when spread to such-and-such network would affect so-and-so persons.

All of these complications come with simply working with non-traumatised people! I can only imagine the complications that come with working with people with serious trauma.

Oh, I didn’t mean to write “non-trauma victims”. I meant to write something along the lines of “non-trauma informants”. The people I work with are everyday folks in West Africa. I try not to say more because I’m keeping both my identity and theirs hidden 🙂

1. Re: “I’m not trying to be snotty here; I think it’s a real concern.”

Jina, I think you are being snotty about the background for Ms. McClelland’s twitter page.

2. Re:”I have three problems — huge, huge problems — with this:”

From Twitter (9/18/10) :

MacMcClelland

For the record: The Haitian group helping Kerby told me she gave a TV interview before I arrived, and her story is well-known locally.

MacMcClelland

This victims-rights org, run by victims themselves, condoned my ride-along and writing about the case, as did Kerby and her mother.

MacMcClelland

I do not presume to question a woman’s right to tell her own story, nor to tell her she is not sophisticated enough to provide that consent.

MacMcClelland

I of course have DEEP concerns for trauma survivors’ needs—as well as about the unconscionable sin of continuing to ignore this epidemic.

MacMcClelland

Future inaccuracies about my role in a story can be avoided via standard reportorial practice of contacting me or my editors for comment.

MacMcClelland

To support the group that supports women like Kerby, send donations here:

http://mojo.ly/bn5Wz8

Thanks, Janie. I appreciate you taking the time to wander over to my blog from The Atlantic Wire. It would have been really helpful if this kind of context came about before the tweeting started, rather than a few days later. In fact, just that kind of local context — that Kerby was well-known locally, that the victims rights org is run by victims themselves, and the nature of the consent are all details that would have left those of us (and I wasn’t alone) raising eyebrows at the beginning more prepared to trust what was going on. We journalists talk a lot about the obligation to keep readers’ trust in what we say — the way the words unfold on the page. We don’t talk that much about how to gain and keep readers’ trust in terms of how we work. I think that’s also important, and this is one example of why.

Trauma reporting always involves deeply difficult decisions. I share with Mac a belief that it’s not a journalist’s place to tell someone they can’t tell their story; you’ll see me lay out exactly this argument in my explicit writing on the subject in the 2009 Liberia blog post to which I have linked in this conversation.

I hope Mother Jones keeps their dogged focus on this issue, and I hope they continue to experiment responsibly with new media in doing it. As I have said, I think it can be done — and as I told them on Twitter, and I’ve said here, I think they usually do important, responsible journalism. I just don’t think this was one of those times.

This helps to set it in context. It still makes not sense for why McClelland is twitting the story although the concern for twitting has shifted a bit.

The question now is is McClelland twitting the story because she desires to put on display for the public in a live way, her own fascination with the rape victim, whom as I understand is named Kerby? It highlights some of the egoistical aspects (and therefore problems) of twitting live when a large tint of that interest in twitting is the “hey look at me! I’m talking to a rape victim! LOOK!”

That would be absurd.

If this really disturbs you, why not contact the reporter directly.

I believe this is the same question you put to me on Twitter. At the risk of repeating myself, I’ll give slightly more explanation than 140 characters allows: Given that the situation was on-going in real time, I tried to reach the appropriate editorial staff at the magazine by phone. I did this out of respect for the journalist; I also work as a journalist, and in a situation like this, where an ethical concern is raised, it would be my boss’s call.

I was replying to Thib’s comment.

Are you also Thib?

Ah, there’s so many people involved in this convo, it’s getting confusing! Though it may just be me and my wordpress software — comments don’t layer for me the way they do on the site, but the site’s too slow to load in rural Rwanda so I manage all the comments only thru the backend. Sorry to create confusion. If you can throw in the name of the person you’re talking to, that’d help (me anyway).

Alas, nope, not Thib. Wish I was a trained anthropologist and a working journalist (and also, while we’re at it, a better violinst) but a girl’s only got so many hours in a day…

No, Jina isn’t Thib. Thib is an anthropologist who works in West Africa.

I’m amazed that Jina can get such good internet access in rural Rwanda!

To reply to Janie, being disturbed doesn’t necessary mean I have the desire to contact the author to ask her about it. And futhermore, it is not an obligation of mine to contact her for clarification. The obligation lies with the journalist, McClelland, to clarify context. In other words, the problem similar to what Jina mentions is that context for the event IS NOT provided, or if so provided, done so very POORLY. Without the journalist providing the context, she comes across as being insensitive to Kerby (the rape victmi), and also comes across as being egoistical (more interesting in “LOOK AT ME TWITTING!” than the actual story of the victim).

It’s the journalist’s duty to properly set that context when it is not easily discernible. When a journalist publishes in a newspaper, associated with the format of the newspaper is a whole line of things including authority, fact, and sensitivity to the people discussed in the story. Twitter does not automatically provide for that kind of context and therefore McClelland needs to be aware of setting the context straight.

There are other kinds of contexts that are part of writing that do not have to do with the format of the publication (whether Twitter or traditional broadsheet). I won’t discuss those because Jina has done that very well in several comments above mine.

Good luck working in Rwanda, Jina! What a privilege to have a job that enables you, it seems to go from place to place in Africa.

Jina, perhaps you should remember what you wrote about another person you critiqued.

From : https://www.jinamoore.com/2010/02/05/rape-victims-nick-kristof-replies/

“I’ve fired scathing blog posts right off before, about this very issue and aimed directly at other pieces of journalism; I regret that. I think I would have learned more — and maybe you readers would too — if I had been more measured and talked first to the journalist whose work I critiqued.

So I started where a journalist should: investigating my assumptions.”s

Yes, I do believe you should have “started where a journalist should”.

That would have been most helpful, don’t you think?

Janie, I think we’re never going to agree. And that’s fine. But every comment that gets added gets pinged to everyone else who has commented, and at this point, it’s you and me going round and round. As I indicated to you on Twitter, I’m happy to discuss any of this further with you by email; I’ll send you a few thoughts privately in a moment.

But I think this topic has probably worn out its welcome in my followers’ inboxes. So I’m going to close the comments section. If anyone would like to issue a raucous protest, leave a comment and I’ll consider your protest. If I don’t publish it, I’ll at least respond to you privately.

Thanks to all for the fascinating discussion.

As a humanitarian aid worker with experience assisting rape survivors in several contexts where sexual violence is disturbingly prevalent, it is NEVER ok to retell a survivor’s story unless you receive explicit consent. Sexual violence is not a sensational story upon which you build your social media career – it is someone’s very real and very personal trauma that s/he will be coping with for the rest of her/his life.

It’s safe to assume that if McClelland was riding in the car with the victim whose tongue was bitten off there was not enough time to give consent. If I were currently working in Haiti, I would report her for journalistic misconduct immediately. Unfortunately new types of media such as Twitter make it difficult to maintain the safety and security of rape survivors, whose stories should be private and only shared with the consent of the victim.

A quick visit to the UNFPA or UNICEF website will provide information on the three most important aspects of assisting rape victims – consent, confidentiality and providing as much safety for the victim and the service provider (nurse/doctor, counselor, etc.) as possible. (So including the rape victim’s name is a flagrant abuse. I sincerely hope it was fake.)

I am not a fan of Twitter and this “rape tweet” does nothing to assuage my fear of misusing information. I understand that this is my personal opinion, however, so I won’t take this point any further!

Many thanks to Jina for highlighting this important debate.