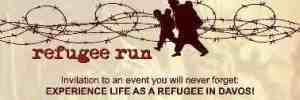

You remember the refugee run, right? Where all the political big shots at the Global Risk Forum could learn what it’s “really” like?

Earlier this week, Scott Gration, Obama’s special envoy to Sudan, tried to diffuse the controversy that’s been swirling around his policy statements (more on that below). He made a personal appeal to the advocates and observers who have taken him to task for, among other things, suggesting the displaced families in Darfur should start thinking about going home. He didn’t mean it that way…really.

I also know firsthand the personal toll of war and what it means to be displaced. Growing up, my family was evacuated three times from our home in the Congo, and we became refugees.

A little IHL 101: Refugees are people who cross borders fleeing their homes out of fear of death or persecution (“internally displaced people” do this without leaving their country of nationality). They can’t go back to their home country, and usually they can’t stay permanently in the country they land in. Voila refugee camps, full of stateless people.

I can’t imagine Gration and his family were stateless. They were missionaries, and though I haven’t checked the paperwork on their country of origin (I’m waiting for someone to call for his birth certificate), I’m pretty sure the decorated American fighter pilot is an American. And I know it was the 1960s, and most of our airplanes were busy, but I’m also pretty sure the US evacuated its nationals during the Congo crises. (Yep.) A helicopter ride, even a rushed one, out of a country descending into violence would be the preferred way out, except that actual refugees aren’t ever allowed on those things.

Earlier this week, Gration released a…statement? Personal essay? Policy prescription?…anyway, a thing, called “This I Believe.” (I also hoped it was an audio essay, but alas.) Designed to set the record straight, it dove first into Gration’s own autobiography. He learned to walk in Africa. His first words were in Swahili. He feels refugees’ pain.

That’s all well and good, but no one is saying he doesn’t like Africans. I’m sure some his best friends really are Africans. The problem he has isn’t that his naysayers think he lacks empathy; the problem he has is that they think he’s wrong. Not about how much he loves Africa, but about that boring old thing called American foreign policy.

Here’s why:

Gration has confused a lot of people since his much-anticipated appointment as SE in March. He denied Sudan was a state sponsor of terror, a move seen by some as a gesture toward better relations with Khartoum even as the Darfur question (literally) burns. He told IDPs they “have the opportunity to move back to a place of their own choosing and to be able to live in safety and security and dignity,” though they disagreed (and he has, “I Believe,” since backtracked). He tried to underplay

al-“I’m the first man ever charged by the ICC with genocide”-Bashir’s expulsion of NGOs (“There’s food! There’s water! But…about that rape protection, the thing is…”). Oh, and he declared the genocide over.

These are all things that, unsurprisingly, Sudan likes. They feel like a slap in the face to the

many advocacy groups that have been pressuring for more effective action on Darfur since 2004.

They are also part of a bigger issues in the Obama Administration. Gration is out front as Obama’s carrot man in a foreign policy hot spot, in the midst of a pissing contest about who really runs the diplomatic show (and with Bill’s cameo-in-absentia in Congo, that question just got a little more piqued). Advocates have not been shy about calling on the administration to get it together, already.

Alas, the problem is bigger than Darfur and Sudan, or Obama and Clinton (either one). Each of Gration’s controversial moves makes sense, if you’re reading from the Engagement Playbook. Soften the rhetoric, dangle the carrots more clearly, change the narrative: These are all things the Left signed up for. This is The Change, or at least the first draft of it. But President Obama is less accessible than Candidate Obama, and it’s unclear how much leverage even the smartest advocates will have to make principled opposition to Khartoum mesh with Obama’s Engagement. Once you’re inside the White House, I’m betting, “Yes we can” can turn pretty quickly into “Yes, we can hear you…but the acoustics in these round rooms are terrible, and we’ve decided to take this in a different direction.”

If anyone knows better than me — and that should be pretty much all of you, since I’m writing this from my Brooklyn apartment, and the closest I’ve ever been to a round room is a — do advise.